We are looking at two photos next to each other. Both show a hand in front of a black background which seems to be the right hand of the same person, most likely a male. In both photos, the palm of the hand is facing the camera and the wrist is visible.

In the photo on the left, the index and middle fingers are pointing up, stretched away from each other, forming a V. Other fingers are closed: thumb is folded over the ring and pinky fingers.

In the photo on the right, the index and middle fingers are again pointing up but they are adjacent. The ring finger is closed, the thumb is folded over it, holding it down. The pinkie is pointing up.

The above is a literal description of what one sees in these photos at first glance. This “initial recognition” stage is called denotation in semiotics. The sign resulting from it becomes a denotative sign.

This is quite important, particularly for those involved in the arts: No sign can stay “as is,” without moving beyond the denotative level.

Let me try to explain: The above descriptions of the photos seem to be quite “objective,” but, actually, we are using the information we have learned and stored. We have learned that what we see is a hand (not a knee, foot, table, spinach) and that a hand has fingers, an inside, an outside, etc.

And, our brains do not just say “these are hand photos” and let it go, but immediately jump to new semantic levels. For example, we try to see if there is anything symbolic about the images: The hand on the left seems to be doing the victory sign, known in most societies, whereas the form in the photo on the right is not a familiar one (Yoga people may recognize it as the “Surya Mudra” position). When we do not recognize the form, we inevitably ask questions like “Does this form have a meaning that I do not know?” or “Why are these two photos next to each other?”

That is, the perceiver, knowingly or unknowingly, sails away from the level of denotation, trying to interpret (attribute meaning, make sense) according to the context and “hidden” signs, with each step (sign) giving way to yet another — a process like opening the Russian nesting Matryoshka dolls. This post-denotation process is called the connotation stage and the signs that develop are called connotative signs. These signs are characterized as “signs of signs.”

For example, the person reading these notes knows the “context” here: When s/he sees the photos above, s/he will guess that they are there to exemplify something related to the performing arts. Yet, if this person sees these photos on a wall of an art gallery, it is likely that s/he will think, “This is an artwork since it is put on the wall of a gallery and some aspect of it must be making it worth exhibiting” because s/he has learned that galleries have people who evaluate and select visual art pieces that deserve exhibition.

As Roland Barthes had pointed out, denotation is often a conscious process, while connotation is a subconscious process. These two levels are not clearly separate from each other – “misreading” the connotative sign as denotative is a pretty common mistake we make. This fallacy can be taken advantage of by some and used for the deception and exploitation of others. (Barthes (1977), 109-121; Fiske, 85-91)

As Roland Barthes had pointed out, denotation is often a conscious process, while connotation is a subconscious process. These two levels are not clearly separate from each other – “misreading” the connotative sign as denotative is a pretty common mistake we make. This fallacy can be taken advantage of by some and used for the deception and exploitation of others. (Barthes (1977), 109-121; Fiske, 85-91)

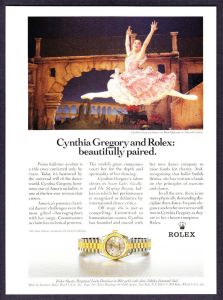

Ballerinas in “beautiful” positions are sometimes used in jewelry and clothing commercials. These commercials do not say “look at the ballerina” or “see how beautiful the ballerina is,” but they say “see how beautiful our necklace is.” The denotative sign (starting point) is no longer the ballerina or the position of her body, but the attribute (beauty) the image connotes.

Ballerinas in “beautiful” positions are sometimes used in jewelry and clothing commercials. These commercials do not say “look at the ballerina” or “see how beautiful the ballerina is,” but they say “see how beautiful our necklace is.” The denotative sign (starting point) is no longer the ballerina or the position of her body, but the attribute (beauty) the image connotes.

Roland Barthes asserted that certain social significations are aimed at concealing or blurring the denotative levels to bring the connotations to the front and make them look denotative. Barthes used the term “myth” to identify them.

In that respect, we can say that nothing is “beautiful” or “ugly” at the denotative level, but there are things considered or accepted to be beautiful or ugly in society. If we wonder why some sign connotes a certain quality and decide to explore, we often reach reasons related to some physical functionality in the origin.

In that respect, we can say that nothing is “beautiful” or “ugly” at the denotative level, but there are things considered or accepted to be beautiful or ugly in society. If we wonder why some sign connotes a certain quality and decide to explore, we often reach reasons related to some physical functionality in the origin.

I will paraphrase a good example given by the media scholar John Fiske:

When you put a man and a woman side by side, you can see the physical features that make the man a “man” and the woman a “woman.” The woman’s body is designed to give birth and breast-feed while the man’s, with bigger and stronger muscles and bones, is more suited for physical struggle with nature. These conditions are accepted to be “natural.”

Yet, the woman’s ability to give birth and breast-feed gets associated with affection, caregiving, “nest building” and house work and becomes part of her “natural,” therefore, de facto definition. And, “naturally,” the physically stronger man becomes the party that finds and brings food. These associative attributes eventually form the “belief” that family is the primary and the core unit in social framework.

Then, thousands of years pass, we come to the twenty-first century and we look at those controlling the political and social mechanisms and see that the vast majority of them happen to be men! What do these positions have to do with birth-giving, breast-feeding, muscle-strength? Nothing. The validity of such qualifications have expired long time ago but the myth is still in control. According to Barthes, myths remain valid by obscuring or disguising their origins, mostly by “naturalizing” history. And myths are kept valid and referred to as “natural truth” by those benefiting from them. (Fiske, 87-91)

Denotation and connotation are possibly the most important issues to be considered in artistic communication:

We run into a certain logic in contemporary arts: Since every person interprets a sign according to his/her own acquired information, since connotations for each person are different, then I can be concerned only with the denotative level when producing my artwork and let it function only as an activator of connotations. We see this type of thinking particularly in the visual arts.

For example: Let’s imagine that an installation artist places a tin can in the middle of an empty art gallery. If you ask what it is, s/he can say “it is a tin can.” So, the object in this setup is just what it is: each viewer can interpret it according to the connotations the tin can triggers in his/her mind. This makes sense, right?

However, there are a few things the artist needs to take into consideration. Most importantly, it is almost impossible for the viewer to enter the art gallery (especially in a town where modern art galleries exist) and look at the tin can on the floor and recall some experiences s/he had with canned food. Since the viewer enters the gallery to look at artworks (because of social codes and frames), the denotative identity of the object will already be a work of art in the form of a tin can, not a tin can as is.

In this example, the chain of connotative signs referred to, to signify the object, starts with paradigms related to the visual arts. That is, the denotative recognition starts from the connotative level. It is not possible for a viewer (interpreter) who enters the gallery to look at works of art and avoid the matrix. The exhibition of the object at the gallery, the information about the gallery, the artistic activities that take place in town, things being said about the visual arts, information about similar works in the history of the visual arts, etc. will not leave the viewer alone.

If this work of art was exhibited, say, in the 1910s in New York, that tin can could be sitting at a museum now as a priceless historical item, because putting a tin can in the middle of an empty gallery as a work of art for the first time would have been a radical “statement,” a critical “manifesto” questioning or defying the tradition. Today, we perhaps can see such work only in some remote place unaware of the “grand tradition” or the “canon” in the arts.